Dear Translators: Let’s Talk about Punctuation Marks

I hope the cartoon has convinced you that punctuation marks truly matter.

If so, read on!

On LinkedIn, I don’t need to see the name or profile picture to guess that someone claiming to hold a Chartered Financial Analyst (CFA) designation is probably Chinese. How can I tell?

Their punctuation gives it away. Instead of using English parentheses (CFA), they use Chinese ones (CFA), which suggests that their keyboard was set to Chinese when they typed it.

Another common example is when Chinese speakers include an English alias alongside their name but retain the Chinese parentheses. Can you spot the difference? Pay attention to the spacing.

English parenthesis: Xiaofen (Alice) Fan

Chinese parenthesis: Xiaofen(Alice)Fan

Similarly, in Canada, you can often tell someone is Francophone just by spotting «guillemets» in an otherwise English sentence.

Following punctuation rules and conventions of the language one is writing or translating into is a mark of professionalism, particularly for language professionals. As an ATA-certified translator for both Chinese-to-English and English-to-Chinese translation, I often find myself reviewing and proofreading documents translated between the two languages—often by experienced professional translators. Yet, time and again, I notice errors in punctuation usage that affect the overall quality of the work.

Same Thing? Not Really

Here is a list comparing punctuation marks used in both (Simplified) Chinese and English that look different in terms of shape, spacing, or usage:

This table highlights the differences in how punctuation marks are rendered and used in the two languages, with Chinese marks typically being full-width—a detail often overlooked by the untrained eye.

Getting Names Right: Machine Translation Misses the Mark

When translating foreign names into Simplified Chinese, the standard practice is to use an interpunct (a “middle dot”) to separate the first and last name, as in 约翰·列侬 (John Lennon). Any other method is considered incorrect.

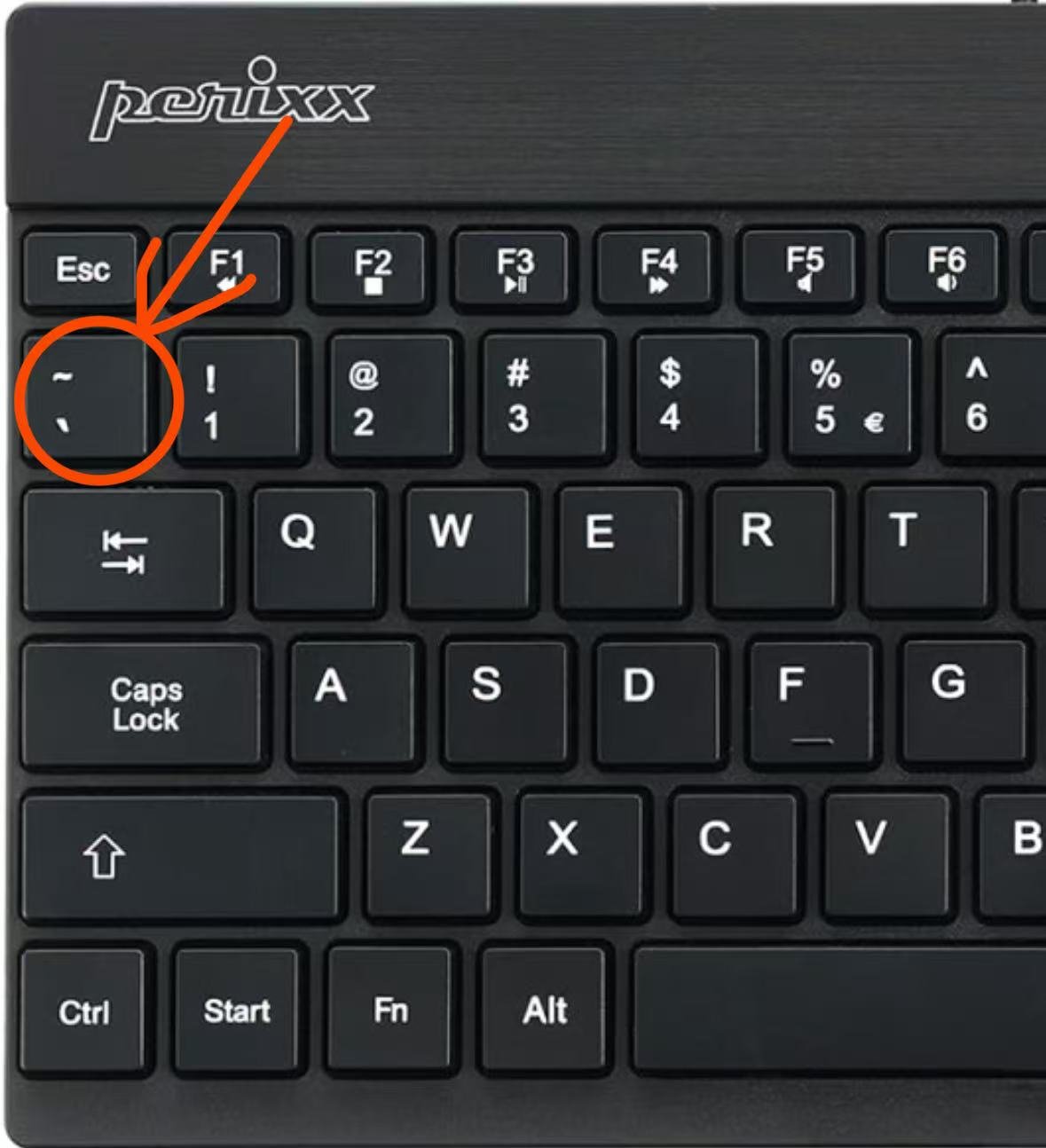

On a QWERTY keyboard, the easiest way to type this interpunct is by using the ` key located next to the number 1, but the computer keyboard must be set to Chinese to be able to do so.

Surprisingly, even an advanced machine-translation tool like DeepL, which is widely praised for its accuracy, gets this wrong. DeepL stubbornly uses an “en dash” as the separator, producing 约翰-列侬 instead of the correct 约翰·列侬.

Underused Punctuation Marks in Chinese

Many punctuation mistakes arise when organizations opt not to hire professionally qualified human translators. However, even skilled human translators sometimes miss the subtleties of proper punctuation. Take the Chinese title mark (书名号) and the pause mark (顿号), both of which do not exist in English. Interestingly, many English-to-Chinese translators, perhaps due to the effort they put into mastering English, seem to underuse these marks in their translations.

For instance, translators sometimes adhere too closely to the source text, reproducing English commas even when the pause mark (顿号) would be more appropriate in Chinese.

Example:

Original English: I like apples, bananas, and oranges.

Correct Chinese: 我喜欢苹果、香蕉、橙子。

Incorrect Chinese: 我喜欢苹果,香蕉和橙子。

Such mistakes highlight the importance of understanding how punctuation functions differently across languages and applying these nuances in translation work.

The Unspoken Punctuation

Finally, I’d like to share a recent observation from my work as an interpreter. One significant challenge for AI-powered natural language processing (NLP) lies in handling unspoken punctuation. In an example I encountered recently, a corporate executive described how Hurricane Debby disrupted her travel plans, saying she “finally got in about one thirty two o’clock last night.”

Any human interpreter would immediately understand that she arrived roughly between 1:30 and 2:00 AM the previous night.

However, when her speech was transcribed by Otter.ai, the result was: “I finally got in about 132 o’clock last night.”

The AI misinterpreted the unspoken punctuation between "one-thirty" and "two," revealing a limitation of algorithms trained primarily on written language rather than spoken language.

I share this example not to dismiss the progress of AI, but to highlight one area where human interpreters still have a clear edge. Mastering the nuances of punctuation—spoken or written—is one of the many things we must do to future-proof ourselves.

Rony Gao is a prize-winning conference interpreter, certified translator and communications consultant based in Toronto and serving clients worldwide. He is a member of AIIC and regularly provides consecutive and simultaneous interpretation services for the Government of Canada, international organizations and global leaders in business, technology and academia.